Gob and Johnny Song

Note

Jim Kenworth arrived at the Croydon Warehouse Writer’s Workshop in 1997 (which I co-ran with Sheila Dewey). His arms were full of scripts which were poetic, allegorical yet absolutely contemporary. I was attracted to and felt an affinity with his writing. Both Sheila and I felt that he was worth the Warehouse developing. We chose one of the scripts, Johnny Song, to be the main event in that year’s Workshop contribution to the International Writers Festival. It was a great success with the audience.

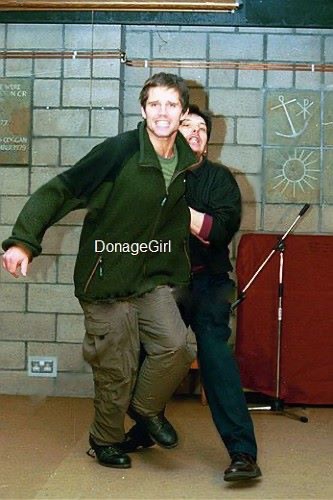

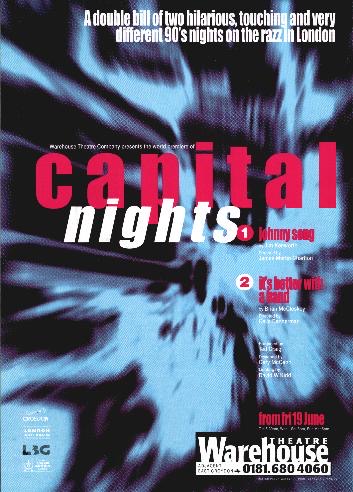

Ted Craig, Artistic Director of the Warehouse, suggested that they produce Johnny Song in a double bill with another one act play developed via the workshop, It’s Better With a Band by Brian McCloskey. I directed the production of Johnny Song as part of a double bill entitled Capital Nights. Johnny Song shows the misadventures of a street poet and a drummer as they wander the streets of the city. They encounter various colourful denizens. Johnny and the Drummer Boy attempt to rouse them with poetry and rhythm. The play combined verse, drumming, larger-than-life characterisation, occasional back-scoring, a wistful belief in the power of poetry. It stood in stark contrast to the acerbic barbs and human frailties of It’s Better With a Band (which Celia Bannerman directed). The plays didn’t rub well together. Jim’s unique voice needed a different kind of showcase.

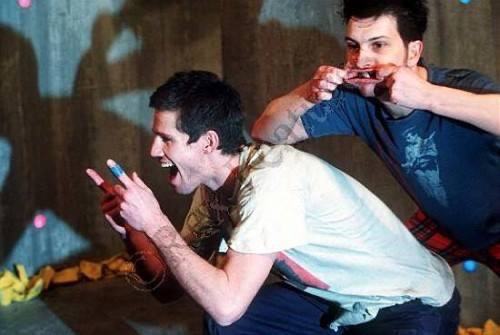

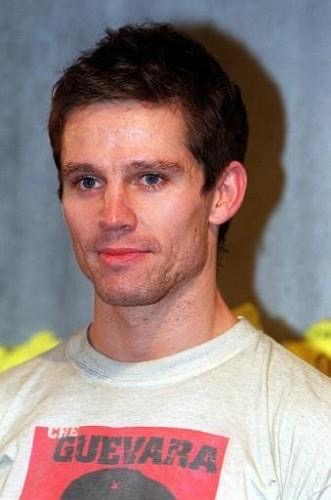

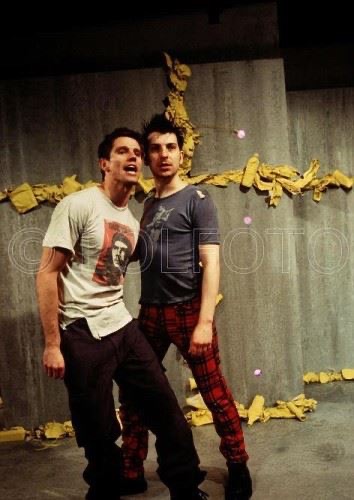

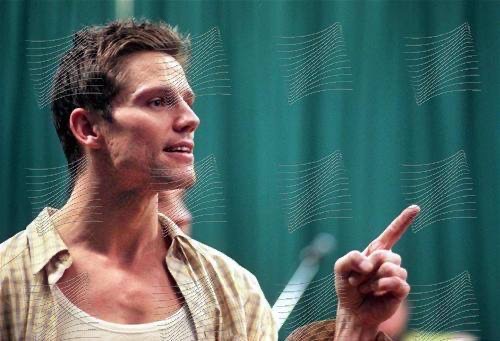

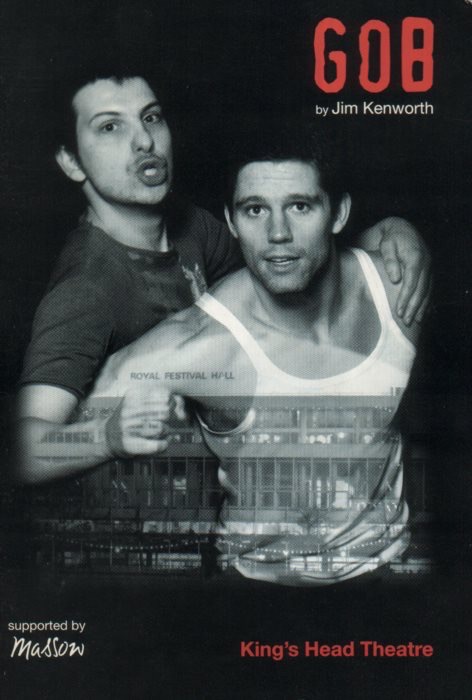

Even as we were working towards the production of Johnny Song, we were showcasing a new Kenworth play, Gob, in Brighton. This features two street poets, invading the Southbank Centre, having a poem-off with a pair of middle-class poseurs. We spent time honing Gob into a short, sharp 80-minute piece. I encouraged Jim to cut a lot of extraneous material; to develop the characters of the two rival poets. He blue-pencilled reams, left pure gold. The two poseurs became mighty characters in their own right. Two actors would play both sets. By the time we showcased Gob in London, Jason Orange of Take That was one of our performers. I’d seen Jason in Killer Net on TV. I felt The Liberator needed a charismatic, charming presence, cutting against the abrasiveness of the role. We sent Jason a script. He liked it. We auditioned him (twice). He was in.

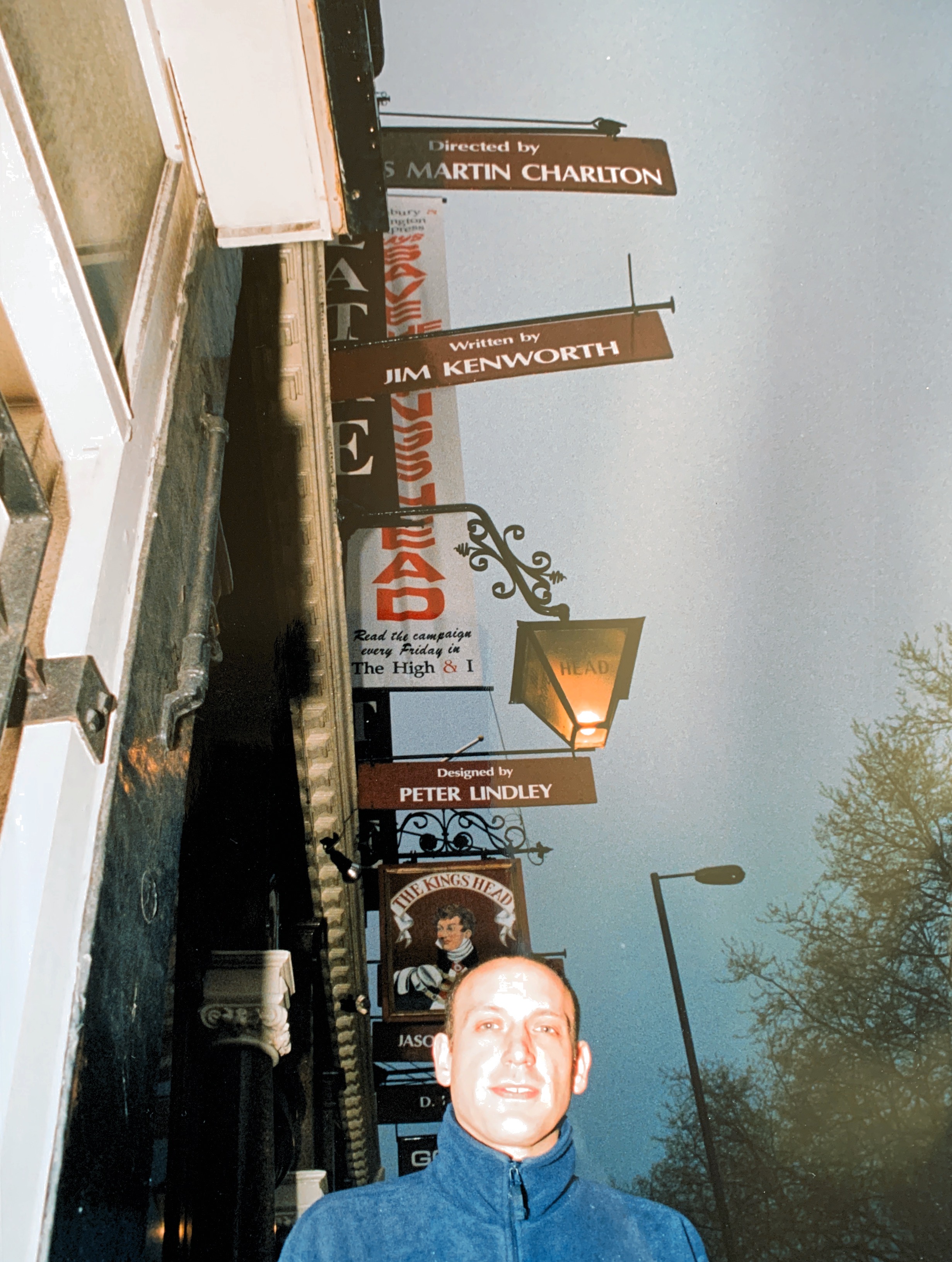

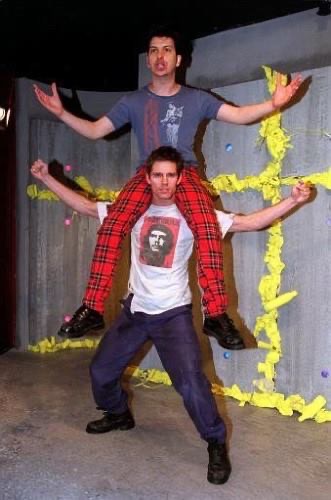

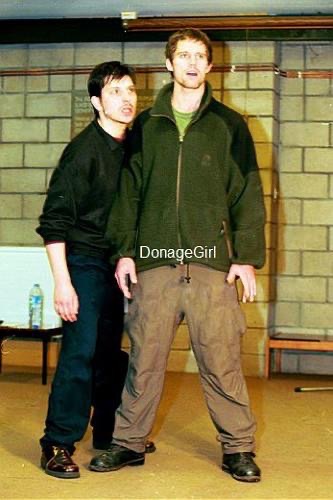

We’d a circus on our hands when he co-starred in the 1999 production. There was huge press interest in a pop star stage debut. My company Friendly Fire co-presented Gob at the King’s Head. Tom Hayes, a regular collaborator who starred in many of my plays and production, was Hard Man Les. Peter Lindley designed a marvellous set which transformed itself from the streets to the Southbank institution. I put a live DJ on stage, to constantly back-score the action. I knew that the play needed stylish movement, physical comedy, giant characterisations, moments of stillness and lyricism, beautifully spoken verse. The two actors were able to provide it all.

We were a sell-out and critical success at the King’s Head. We were due to take the play to the Edinburgh Fringe but Jason decided not to pursue the acting. The co-producer got cold feet and withdrew the finance. At least we had the London run. Kenworth was established as a playwright. I had my biggest directorial success so far. So, good.

Productions

Johnny Song

Reading: Writers Workshop showcase, International Playwriting Festival, Warehouse Theatre, Croydon, 21 November, 1997

Cast: Helen Grear (Prostitute/Madwoman), Thomas Murphy [Tom Hayes] (Drummer Boy), Paul Viragh (Vagrant/Skinhead), Lee Whitlock (Johnny Song)

Directed by James Martin Charlton; percussion by Sherry Beckett

Production: As half of Capital Nights, Warehouse Theatre, Croydon, 19 June – 12 July, 1998

Cast: Charlie Foloronsho (Drummer Boy), Matthew Fraser (Johnny Song), Victoria McFarlane (Vagrant/Skinhead/Prostitute/Madwoman)

Directed by James Martin Charlton; designed by Gary McCann; lighting by David W. Kidd

Produced by Ted Craig for Warehouse Theatre Productions

Gob

Reading: Final Edit/Friendly Fire Productions at The Marlborough Theatre, Brighton, 19 May, 1998; repeated Drill Hall, London, 15 September, 1998

Cast: Daniel Harcourt (The Liberator/Tarquin), Thomas Murphy (Hard Man Les/Crispin)

Directed by James Martin Charlton; lighting by Lisa Audouin

Showcase: Friendly Fire Productions at King’s Head, Islington, 7-8 February, 1999

Cast: Tom Hayes (Hard Man Les), Jason Orange (The Liberator)

Directed by James Martin Charlton; assisted by Rosalie Clayton; sounds by DJ Spike

Production: Friendly Fire Productions/Bishops Rode at King’s Head, Islington, 16 March – 18 April, 1999

Cast: Tom Hayes (Hard Man Les/The Darling Boy), Jason Orange (The Liberator/Mike Nietzsche)

Directed by James Martin Charlton; assisted by Rosalie Clayton; directed by Peter Lindley; lighting by Lisa Audouin; sounds by DJ Spike

Produced by James Martin Charlton for Friendly Fire Productions & Michael Culkin for Bishop’s Rode

Press/Audience Reaction

Johnny Song

"Nice idea, two short plays about London after dark. Presented at the Warehouse, the first, Johnny Song, by Jim Kenworth, is directed by playwright James Martin Charlton and there are evident similarities in their work. It is a curious, lively piece, focusing on Johnny Song, a poet/dosser (spiritedly and beguilingly performed by Matthew Fraser) and his mate Drummer Boy (Charlie Folorunsho), who go about the city trying to elevate people with their bad poetry and drumming. Charlton's direction keeps things moving and Kenworth, like the director, has an interesting use of rhythm, dropping in faux-Shakespearean couplets and strange lyricism." - Adrian Dawson, The Stage

Gob

“You've met Lenin, Trotsky and Fidel Castro. Now meet the Liberator, a people's hero who uses "the last weapon of the weaponless" — his gob. In fact, complete with Che T-shirt, the Liberator owes more to his fictional counterpart, Wolfie of the Tooting Popular Front, than he does to any Marxist agitator. But whereas Wolfie was a seventies figure, the Liberator is a nineties hero down to his sweetly touching belief that personal growth is a revolutionary statement. It's up to him to teach Hard Man Les that it's all right to be soft, but we need to put the poetry back into politics first — you don't need a rifle when you can rhyme moon with June. So off the Liberator goes into the dark of the London night to storm that bastion of privilege, the Royal Festival Hall, scene of Tony Blair's May 1 victory celebrations and many a dodgy poetry reading. Here the tongue rucking begins in earnest as Liberator and Les take to the stage and preach sedition with only a little help from iambic pentameter. Jim Kenworth's play — and it's stretching the imagination a bit to call it such — is an appealing and occasionally irritating mixture of the tongue-in-cheek and the preposterously serious. It is also an example of a small but growing theatrical trend that aims to create a club-like ambience for drama. It's not intended for those who lived through the seventies, but those who were born there. DJ Spike mixes the tunes on the sound system as Liberator and Les go on their New Age quest. Kenworth's script and the production both borrow too heavily from early Berkoff, but it has some wry jokes, a perky cartoon energy and it is punchily performed by Tom Hayes and ex-Take That star Jason Orange. No, it won't change the world, but for 70 minutes it gives you a small but distinct high and I can't protest at anything that promotes the hardly seditious idea that if you have a voice then you should try to make yourself heard." - Lyn Gardner, The Guardian

"The time is nowish, the place is here or hereabouts, and two angry, idealistic members of London's homeless underclass are out for revenge. Jason Orange, apparently once a member of a pop group of some repute, is The Liberator, a rebel-poet dreamer in the tradition of Citizen Smith and Rik from The Young Ones; Tom Hayes (The Bill) is Hard Man Les, his short-fused psychopathic sidekick. Together they rage around the West End in their Che Guevara and Clash T-shirts, in a doomed attempt to relight the fire of revolution in the South Bank Centre and Leicester Square. Directed by James Martin Charlton, Gob is innovative — a genuine two-hander cast even shift their own scenery), it uses a live DJ to deploy the sound effects and cleverly represents several London locations with little more than a minimal breeze-block backdrop. But Jim Kenworth's script suffers from an inability to decide whether it's a satire on the folly of youthful rebellion, or a genuine, non-ironic call to arms. As such, it stands or falls on the performance of its two stars. Fortunately, Orange camps it up magnificently as the zealous mob orator, staring into the middle distance and quoting Marx to the strains of Jerusalem. And if his acting skills are still a little rough around the edges and you can never stop thinking 'Take That!' – his sheer physical presence is magnetic. If 90% of acting is body language, Jason Orange has got it sewn up: this boy can move. Putting six years of boy band choreography to fine use, he's all sudden spins and graceful glides and even throws in a backflip, delighting the sizable contingent of 18-year-old girls in the audience who probably grew up with his poster above their bed. Hayes is fantastic too, especially when being his alter ego; a spectacularly camp actor. The real star, though, is the Wonderful King's Head itself which other theatre can you sit within spitting distance of an early Nineties pop icon and enjoy a pint at the same time? And with the London Board threatening to withdraw funding, it may be pleasure lost to us. Go see Gob before it's too late." - Simon Price, Metro

"When Jason Orange was a Take That boy he played to arenas of screaming teenie girls (and boys). Now, apart from the inevitable court cases, Take That is pop history, Rob is soaring to even higher stardom, Gary is coasting, Howard is writing songs and on the press night of Jim Kenworth's new play, little Mark, whose solo car seems to have dipped, is wearing what looks like a pixie hat in the back row a tiny theatre in Islington watching Jason making his London theatre debut. Old Take That fans won't see Mark perched here every night, but they will see Jason for the next couple of weeks proving that he's not just a pretty face with finely chiselled cheek bones. Maybe the guy won't shake off the Take That tag too easily, but he can act he looks totally at ease on stage an he's surprisingly good at comedy Fortunately, after a few minutes you forget the old image and enter into the cartoon world of Kenworth's venomous two-handed farce about a couple of no fixed-abode verbal warriors attempting to demolish that bastion of culture, the South Bank Centre. Jason is The Liberator who wants to release the sound and fury of his gob on the fashionably cool, ironic and pretentious art establishment, while Tom Hayes is his nutter side-kick with a psychotic Glaswegian accent, Hard Man Les. Together these idealistic tee-shirt revolutionaries race across London in their "crusty traveller chic" on a naive quest to seek and destroy the fragrant set who are destroying the ability to express honest feelings. En route, they encounter a whole range of pond life and party animals, including a couple of pretentious poets (one a Greenwich Village fake, the other a campy aesthete), and refill on booze, kebabs and french fries. Backed by DJ Spike's haunting and atmospheric soundtracks, the two actors make a superb double act and between them play all the supporting characters on Peter Lindley's South Bank grey set. Despite the bleak, punky sounding title, the most memorable moments in James Martin Charlton's inventive production are the most lyrical and Jason delivers his long poetic speeches about the importance of being able to open up and speak like a child with genuine artistry. Unfashionably honest, this is a storming play that speaks from the heart for the "broken nosed and the broken apart" , and by the end of Kenworth's compassionate war of words you really do feel that the gob is the last and most potent weapon of the weaponless in Cool Britannia. Step out of the King's Head into the cappuccino cool of Upper Street, NI and you'll see what I mean. Forget Take That, the play's the thing." - Roger Foss, What's On

YOU can see why the King's Head, newly deprived of its London Arts Board grant, liked this play. A new work by Jim Kenworth, Gob lobs an iconoclastic missile at the comparatively cushy and conventional mainstream arts establishment. Or rather at the Festival Hall, which is the villain of the piece. The play's two main characters — one, the Liberator, a cultural hooligan, the other. Hard Man Les, just a hooligan — set out to storm the South Bank. While Les is all psyched up for a good rumble, the Liberator is a self-styled "Gob Warrior'' with higher things on his mind. Poetry, he says, is the last weapon of the weaponless, and anybody should have the right to express themselves in the so-called People's Palace. Onstage they find two performance poets in full flow: a foul-mouthed American named Mike Nietzsche whose poem consists of the single word "Arsehole'', and the Darling Boy, a dreadful drama queen who cranks out much romantic mush about murdered petals. A battle of the bards ensues. You can guess who wins: Kenworth hardly gives his upstarts much competition. As it happens, the Liberator is not a very good poet either, but that (I hope) misses the point. Gob is about freedom, not quality, of expression. Too much of a good thing, you might be excused for thinking, when it results in great globs of cod-poetic hyperbole, but then I suppose that is being elitist too. There is plenty of irony to lighten the load. But the play passionately insists that poetry, if not quite revolutionary, is indeed the means to individual liberty. This is a refreshingly uncynical thesis. Given the emphasis on honest and direct expression, though, it comes couched in mightily pretentious terms. And in its own way —when, for instance, it dismisses clubbers as moronic herd-followers incapable of poetic thought— the play is just as elitist as those who would exclude the unsophisticated from the temples of high art. But for all its cringe-making excess, this is a fresh and sometimes very funny piece, marvellously directed by James Martin Charlton with an acute eye for physical comedy. Two actors play all the parts with well-honed versatility. Jason Orange (formerly of Take That) is exuberantly impassioned, if never completely plausible, as the Liberator. Tom Hayes is spot-on as Les and the Darling Boy. The show is enlivened by the presence on stage of DJ Spike, who mixes in his own witty musical asides throughout." - Nigel Cliff, The Times

"Meet the Liberator. He's going to lead a revolution of London's lost, dispossessed, inarticulate and forgotten ones, releasing them with the 'last weapon of the weaponless', his gob. And he knows where he's going to start: at the Royal Festival Hall, because that's where the government celebrated their shameful 'triumph of packaging' on May 1 1997. The fact that the Liberator is played by Jason Orange, now free from the top-notch packaging of Take That, is a small irony not lost on Friendly Fire's DJ-driven production of Jim Kenworth's new play. In fact much of its entertainment value comes from the culture clash set up by the former superstar's chosen role, right down to his appearance in a famous pub theatre struggling for survival. In a delicious scenic coup, the back wall of the King's Head gets to mimic the South Bank's distinctive concrete. 'Londoners are always the hardest crowd to win over' says the Liberator, and if anyone knows. Orange should. The question is, how long will it be before he gets a gig at the National? Or the King's Head gets proper public funding? Kenworth's play doesn't provide much opportunity for subtleties of interpretation from its actors but it has enormous heart. The Liberator's sidekick is one Hard Man Les (Tom Hayes), a Scotsman stereotypically eager to use his fists in the class struggle. After infiltrating the bastion of 'the fragrant set', the pair have to take on the formidable recitative talents of Mike Nietzsche and Darling Boy in a poetry slam. With a swastika tattooed on his bare chest, maniac butch boy Nietzsche is Orange's finest moment. 'Arsehole' he intones, illustrating his relevance to Kenworth's message about speaking up with your own voice: even if it 'ain't proper'. The character might rule out the possibility of the production being taken on a tour of the nation's secondary schools, which is a pity, because that's where Orange and Gob could really start a revolution." - Time Out

.jpg)